- Home

- Marina Oliver

The Chaperone Bride Page 4

The Chaperone Bride Read online

Page 4

Sir Kenelm stared at her, shocked. Although he had formed no good impression of Captain Frazer, this action of a father in taking his daughter's possessions away in order to gamble was despicable. He wanted to ask if she and her father had ever had to leave without settling their account, but decided it would be too embarrassing for her.

'Why did you not buy one with the money I gave you?' he asked, rather gruffly. It was intolerable she should be deprived of what must have been something she enjoyed. 'Was there not enough?'

Joanna turned and looked at him, a slight frown in her eyes. 'There was plenty, you were very generous, but I did not think it was meant for such luxuries. And I doubt if any Leeds shops would have had guitars.'

'We will send to London for one at once. I have a strong wish to hear you play me some Spanish and Portuguese airs.'

She turned her head away again, and looked out of the window, but he could see her reflection in the window. She was blinking back tears. He stretched out a hand towards her, then drew back. She might not understand it was only for comfort, nothing more.

'You are far too good to me! And it is so little I can do in return. I promise I will be a good wi – chaperone!'

'I am sure you will, my dear.'

After a brief silence Joanna spoke again.

'Tell me, please, about your home. Rock Castle sounds a rather forbidding place.'

'I trust you will not find it so. The original castle is in ruins, but there is still a courtyard, part of the old castle outer ward, which I use for stabling. The house is just over a hundred years old, built in the time of Queen Anne. It is a little distance from the ruins, separated from it by the stable yard. You may find it bleak up on the moors, especially in winter, when there can be strong winds and deep snow that cuts us off for weeks, but in the spring and summer it is magnificent.'

'I was used to bleak country in Portugal, and snow,' she added with a shiver, and pulled her cloak more closely round her.

The chaise was well supplied with rugs, and it was not the cold, he thought, which affected her, but the memory of those days when conditions for the families of the soldiers, even officers, must have been harsh and often unpleasant.

'Most of my servants were born on the estate, and have been with me all my life, and they will be delighted to find I have provided them with a mistress,' he told her. 'My Cousin Georgina, who died recently, was a rather strange woman. She would stay in her own rooms for days at a time, and when we had visitors she often refused to meet them.'

'That seems rather odd behaviour for a chaperone,' Joanna said, and then bit her lip. 'Oh dear, I am so sorry, I should not criticise.'

'But it is the truth. She took little interest in household matters apart from those which affected her comfort. Mrs Aston, my housekeeper, will be delighted not to have to take all the responsibility for managing the household.'

'Won't she think I am interfering if I try to manage it?'

'I know she will be delighted. She is another of my old servants who has known me from when I was in short coats, and she has been saying for years now it was time I remarried. She will welcome you, never fear.'

Joanna did not seem reassured, and was silent for a while. Then she spoke again.

'Tell me about your children. They are twins, you said. Will they welcome a new mother?

'As they have never had one, for Maria died when they were born, they will not think you are taking their mother's place. They were ten in August. Their governess was not, I'm afraid, very successful in either controlling their high spirits, or instilling much knowledge into their heads. I trust Miss Busby will have more success.'

'I hope she does not quell their high spirits too much!' Joanna exclaimed, and once more apologised. 'My wretched tongue! I am inclined to say the first thing that comes into my head!'

He laughed. 'It is refreshing to hear the truth! I shall depend on you to moderate her severity if you consider it too harsh.'

'Me? But – but she is so much older than I am, and while we were waiting to see you, she made it plain she considered me beneath her notice! Oh, I should have thought of this! She will never take orders from me!'

'You are not regretting our bargain, I trust?'

'No,' she said slowly, as though she did not quite believe what she said. 'I find it so strange, though, as if I am still dreaming.'

'If she displeases you, or is impertinent, you must tell me, and I will dismiss her.'

'Oh, I could not! How – how would she go on? How could she find another position if you sent her away without a character?'

'I would not do that. The twins are staying with my brother Henry and his family at the moment,' he went on. 'He has a house a few miles away from the Castle. He has a son of seven, and a baby girl just a year old.'

'Is he your only brother? Do you have sisters?'

'I have another brother, Matthew, who is serving in the army, in a cavalry regiment, and three sisters who are all married and living in the south of England. Henry and his wife Albinia are the only ones you are likely to meet until the summer, when my sisters usually come with their families to stay at the Castle for a month or so.'

He was sure she breathed a sigh of relief, and hid a smile. Time enough for her to meet his sisters when she had become accustomed to her new circumstances.

'Is there a village nearby?'

'A small one, with a church, but most of my tenants live on farms. I will take you round and introduce you when you have met all the house servants.'

*

The village consisted of one street, with an ale house at one end and the church on a hill at the other. They drove straight through and turned up a long drive that curved round past a small lake, and was bordered by oak trees that all leaned one way, battered by the prevailing wind.

Joanna had an impression of a long, low house, surrounded by a garden where high hedges of yew protected it from the winds which were blowing across the moorland to the north and west. Behind and to one side she caught a glimpse of broken walls she assumed were the remains of the original castle, but as an elderly butler opened the door, Sir Kenelm helped her from the chaise and hurried her inside, saying she must get warm, and could inspect the gardens when the weather was more clement. Two footmen were sent after the chaise, with orders to take all my lady's parcels up to her ladyship's suite of rooms.

A plump woman in her fifties was waiting in the entrance hall to greet them, and she bobbed a curtsey.

'Welcome, Sir Kenelm, and Lady Childe. Potts and Venner arrived an hour since and told us the good news. I will have tea served in the drawing room as soon as my lady has been to take off her cloak and tidy herself.'

Sir Kenelm took Joanna's hand and led her forward. 'Meet my wife, Mrs Aston. My dear, Mrs Aston will show you the way. Look after her,' he added to the housekeeper, 'she is still rather bewildered at the speed of our wedding.'

'Of course, Sir Kenelm. I hope you will be very happy here, my lady. Will you come with me now?'

Joanna followed the woman up a flight of stairs which split and curved round to either side. She had never before been in such an elegant house, and she felt a surge of panic, wondering how she was to go on in such an unfamiliar setting. But Mrs Aston was talking, and she forced herself to concentrate.

'I have had a fire lit, and the bed is being aired, my lady. I hope it will be comfortable for you, but we had no idea Sir Kenelm was contemplating bringing home a bride.'

Neither had I, a week ago, Joanna thought, and stifled a giggle.

'I'm sure it will all be well,' she managed. 'Sir Kenelm tells me you have been in charge of the household for – since – that is – '

'Since his first wife died,' Mrs Aston said, and Joanna detected a note of – was it censure? – in her voice. Was it directed at her, or Sir Kenelm? 'We have kept the suite of rooms in readiness all these years, hoping he would find someone else. Here they are,' she added, opening the door into what seemed to Joanna to be a room as big a

s a ballroom.

Two maids were busy making up the bed, while another was removing and folding dust sheets from the other furniture. A huge fire blazed in the grate, but Joanna had little time to look about her, for Mrs Aston was ushering her across the room to another door.

'This is the dressing room, Sir Kenelm's own dressing room connects with it, and his bedroom is beyond, at the corner of the house. Sir Kenelm's late cousin occupied a suite in the other wing, where the guest rooms are, and the children, with their governess, are on the floor above those. Betsy here will look after you unless you have brought a maid of your own? She looked after Miss Georgina.'

'N – no, I did not,' Joanna said, and somewhat hysterically wondered whether she ought to have purchased a maid as well as clothes. 'You must be Betsy,' she went on, as the girl who had been folding up the dust sheets came across and bobbed a curtsey.

'Yes Miss, my lady, I mean.'

'Betsy will unpack your luggage as soon as it is brought up. Now, I will leave you to tidy yourself, and then Betsy will show you the way to the drawing room. Ring for me later if you need me.'

What have I done, Joanna asked herself as she took off her cloak and washed her hands. How can I possibly manage in such a huge house? I've never even stayed in one half as big. I never dreamed Sir Kenelm owned anything like this. He must be much wealthier than I thought. How shall I go on?

*

Chapter 3

During the next day Joanna met most of the indoor servants at Rock Castle, and began to find her way about it. The layout of the house was a simple matter. There was a central corridor on each floor, with rooms to either side. Two wings projected to the rear, one containing the kitchens, still room and bakehouse, the other a laundry and brewery, with storerooms. Both had bedrooms above for the servants. Mrs Aston took her on a grand tour after she had breakfasted.

'For you'll no doubt wish to make some changes, my lady,' she said. 'Miss Georgina did not feel it her business, and I certainly cannot take it on myself to do aught but what has always been done. Many of the rooms need refurbishing, and some of the chairs could be better for new covers, not to mention the need for new curtains. Why, some of them are so rotten we fear to draw them in case they fall to bits. Sir Kenelm, like most men, does not notice such things.'

'Oh, but I can't make such changes,' Joanna protested. She had noticed most of the rooms were a trifle shabby, but as she had never lived in an English country house, she did not know what was considered normal. 'It's not my place to do so.'

'Then whose place is it, my lady? There's been nothing but the most essential repairs done since the master's first wife died. There was no one who cared or wished to make such changes.'

Joanna took a deep breath. 'Then I will consult with Sir Kenelm,' she said, and this appeared to satisfy Mrs Aston.

'I will show you something,' the housekeeper said, and led the way up the narrower stairs which rose to the nursery floor. She explained that there were store rooms on that floor as well as bedrooms for the children, their former Nanny, who still looked after them when they were not at lessons, and the governess, plus a schoolroom and sitting room for the governess. 'We'll have to empty the old nursery soon, no doubt,' she said. 'When the twins grew old enough to have their own bedrooms we used it as a storeroom.'

For a moment Joanna did not understand, and then she blushed to the roots of her hair. There would be no need of nurseries, she thought, for there would be no more babies. A momentary pang assailed her. Once she had looked forward to having babies of her own. She had often helped care for the children of the camp followers in Portugal, but her bargain with Sir Kenelm precluded any such hopes. She certainly did not intend to take advantage of his permission to take lovers, even if he had been prepared to accept any of their children And any such children would not have used these nurseries. She dragged her thoughts away from such pointless speculations.

Fortunately Mrs Aston had moved along the corridor, much narrower up here than on the lower floors, and Joanna followed slowly to allow her blushes to subside.

There were several trunks in the room Mrs Aston showed her.

'Here, my lady, we have stored some rolls of damask her previous ladyship ordered, for she wished to replace some of the curtains. But she was ailing all the time she was carrying the twins, and did not feel able to deal with the seamstress. There is a woman in one of the villages who makes curtains, and she would come whenever you wished. They have been well kept, with camphor and lavender, and if they are not fit for the drawing room and the saloons as her late ladyship planned, they would do very well for the minor bedrooms, and you could order what you preferred for the main rooms.'

'I will ask Sir Kenelm what he wishes,' Joanna said firmly. She was feeling overwhelmed. 'I do not feel ready to make such decisions on my own, not yet. Not until I know the house better.'

Mrs Aston smiled, and led the way back downstairs.

'Of course. I understand. Sir Kenelm will be in his library, I expect. He spends most of his time there when there are no guests. Now, though, there will be more entertaining. You will wish to join him.'

It was a statement, not a question. Joanna did not know what else to do. Sir Kenelm had been out, riding round the estate, she was told, when she came down to breakfast, and she had not seen him since supper the previous evening. She must ask him how he wished her to behave, when he might wish for her company, and when he had business to deal with. They would have to keep up a pretence in front of the servants, and Betsy had already said she was surprised they did not take a wedding journey, perhaps visiting London.

'But no doubt the travelling in winter would not be very pleasant, especially if it's such a terrible winter as last year. I heard the river in London froze.'

'No, travel in winter is never pleasant,' Joanna agreed.

This pretence was, she could see, going to be more difficult than she had expected. Fashionable married people, Susan Howard, one of her friends at school had informed her, did not live in one another's pockets. They had their own circles, went their own ways to parties, and met only when entertaining in their own homes, or taking parties to the Opera. Ladies invariably breakfasted in bed, made calls, went shopping, while the husbands, depending on their interests, spent their time riding, visiting Gentleman Jackson's boxing academy or Manton's shooting gallery, usually dined at their clubs, and afterwards spent the evenings and half the nights gambling.

Susan, the daughter of a Viscount, and a year older than Joanna, should know, but she had not explained how married couples occupied themselves when in the country. She needed to talk to Sir Kenelm and ask for his guidance. After all, he could not expect her to know these things.

She sought in her memory for information from the books she had read, especially the novels. Ladies paid visits to their husbands' farm workers, taking comforts for the sick and advice on everything, but she did not know where Sir Kenelm's farms were, or where the farm workers lived. Nor did she know enough about anything to offer advice. She laughed at the vision of herself carrying soup to cottagers who might belong to a neighbouring estate. Would they be offended, or sneer at her? She did not even know if there were any neighbouring estates. The country had looked very bare as they had driven over the moors on the previous day, and no other large houses had been visible.

If she had to spend her time doing embroidery, or deciding on curtain fabrics, she would find life boring, despite the new comfortable life her odd marriage had given her. Perhaps when the children returned home she would have company, for they surely would not be kept in the schoolroom all the time.

Mrs Aston, saying she had no doubt seen enough for the time being, brought her attention back to the present by indicated the library. The door was firmly closed. Ought she to knock and wait to be invited in? Mrs Aston, perhaps seeing her hesitation, came and opened the door and ushered her inside.

'Go and talk to your husband,' she said, her tone motherly.

Her husband

! She knew he was, but she was still existing in a dream. There was nothing she could do, however, while Mrs Aston watched her, a fond smile on her face. Joanna took a deep breath and walked into the room.

*

Sir Kenelm was seated behind a large desk, but he rose at once and came across to take her hand.

'Are you quite bewildered?' he asked. 'Has Mrs Aston bombarded you with information? Come and sit down, and would you like some ratafia before we take a nuncheon?'

He led her to a chair beside the fire and took another opposite her. She sank into it, finding herself more tired than she had expected. It was due to the mass of information she had been given, she decided, not physical exertion.

Joanna laughed. 'Yes please. I am feeling rather overwhelmed,' she admitted. 'There is so much I need to ask you!'

'I am sorry I had to go out early, but there has been some damage to one of the cottages when a large elm branch fell onto the roof. I needed to persuade the old woman who lives there to move into her son's cottage while it is repaired. She thought if she moved she would never be allowed to go back. If the sun stays out, would you like to ride round some of the estate this afternoon, or are you too weary after the journey? We could spend an hour before it gets dark.'

'Yes, I would like that. I am sure I am expected to know your people. And I have so many questions.'

They went into the morning room and ate ham and fruit, and new rolls with sweet butter, then Joanna changed into her new riding habit and Betsy showed her a way through the kitchen wing to a side door opening into the stable yard. One of the grooms was having difficulty restraining a big black horse, which Sir Kenelm introduced as Mephisto.

'He's rather a devil,' he said, 'and only permits me or Potts to ride him.'

He had ordered Polly, a gentle chestnut mare, saddled for Joanna, and went to check her girths.

'Just until I see how you manage,' he said apologetically. 'Then you can have something more lively. And I must teach you how to drive the gig, for the times you do not wish to ride. Have you driven before?'

Rebel Heart

Rebel Heart Theft of Love

Theft of Love Courtesan of the Saints

Courtesan of the Saints Fatal Slip

Fatal Slip Highwayman's Hazard

Highwayman's Hazard The Cobweb Cage

The Cobweb Cage The Irish Bride

The Irish Bride Apple Blossom Bride

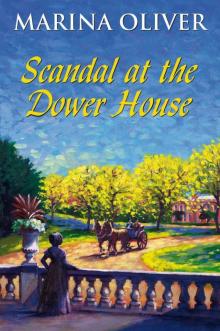

Apple Blossom Bride Scandal at the Dower House

Scandal at the Dower House Eugenie and the Earl

Eugenie and the Earl Her Captive Cavalier

Her Captive Cavalier The Glowing Hours

The Glowing Hours Sibylla and the Privateer

Sibylla and the Privateer The Baron's Bride

The Baron's Bride Player's Wench

Player's Wench Gavotte

Gavotte The Chaperone Bride

The Chaperone Bride A Murdered Earl

A Murdered Earl Charms of a Witch

Charms of a Witch Convict Queen

Convict Queen The Accidental Marriage

The Accidental Marriage